By (Gioele Coccioli, Massimiliano Biggio)

Edited by (Francesco Corbellini, Head of Articles)

Brief political introduction

Italy has returned to the polls early after a turbulent summer: Prime Minister Mario Draghi, after about a year and a half, has seen his majority of national unity fall apart. Ex-President Giuseppe Conte (leader of the 5stelle party) was one of the main actor, opposing a rule regarding the construction of a waste-to-energy plant in the capital, as well as demanding Draghi's attention on social issues such as the minimum wage and the defense of the controversial Citizenship Income. The abstention of the 5stelle on the trust vote represented an opportunity for Forza Italia and Lega, with the latter having long been at the center of controversy with respect to government action. Having lost the support of these three forces, Draghi stepped down.

The September 25 vote was a watershed compared to previous election rounds. Fratelli d'Italia, the only party outside the Draghi majority, took the victory. Analyzing the flows of votes, Giorgia Meloni's party (about 7 million votes) drained support from its allies, particularly Salvini's Lega. After all, the electoral pool of the center-right coalition remains unchanged from the last most relevant elections (European 2019 and political 2018). What has affected the success of Meloni and the Center-right block is first and foremost the increase in abstentionism, which has reached nearly 40% on a national basis. Secondly, Meloni, Salvini and Berlusconi were better able than their opponents to exploit the electoral law, which awards a kind of majority prize through the mechanism of single-member constituencies, which rewards coalitions. Fragmentation on the other side of the fence (Letta, Conte, Calenda) thus exaggerated a success that was in the air.

The victory of Meloni, a candidate to replace Draghi at Palazzo Chigi, represents a risk to Italian democracy according to some observers. Indeed, the leader of FdI (Fratelli D'Italia, ndr) has behind her a history of militancy in the most extreme right-wing circles, as well as a path, that has seen her at the forefront of criticism of European institutions and aversion to financial power centers. However, in the last period she has smoothed out the corners: during the brief election campaign she presented herself as a guarantor of public accounts and international agreements, reaffirming Italy's membership in the Atlantic block and following the Draghi government's line on Ukraine (already externally supported as the crisis unfolded). Draghi himself reassured international fora about the continuity that would emerge from the polls, regardless of who would win the elections. That is goin to undoubtedly be a conservative handling of civil rights, given the political line of the center-right; it remains to be seen whether there will be reactionary moves in this direction, but it would be smarter to avoid the risk of an even worse social situation with protests due to the already pressing economic crisis. What seems to be off the table, to the joy of international investors, is a reckless management of the public budget and international relations.

Market response to Italian elections

Analysing stocks after the Italian elections we can see that in the first moment markets reacted well in fact Italy's FTSE MIB index (FTSE MIB) was up 1.3% in early trade before erasing gains.

Politics is not having the expected impact on markets. We'll have to wait and see if the League and Forza Italia (parties)' worse than anticipated result helps the stability of Meloni's future administration. By the way, the general trend of the FTSE MIB Index is bearish, so it has lost the previous gain.

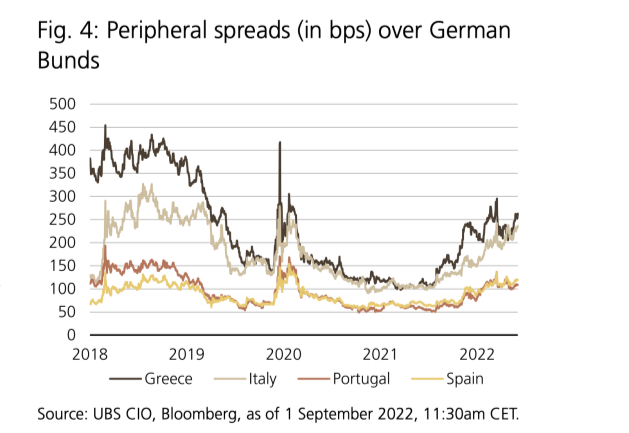

Dealing with interest rates on government bonds we can see that the spread between Italian Btp and German Bund before the elections was 236 basis points, immediately after the elections it was 238 and now it is 242. We can't say if this is related to the new right-wing parliament majority or to the general unfavourable macroeconomic circumstance in which Italy is located.

Future expectations and final forecasts

However, the budget bill, which must be submitted to the houses by October 20th, will be a tough test for the incoming administration.

Compared to the April Def's + 2.4% prediction, the prognosis for 2023 will be almost two points lower. The initial deficit will rise to 5% and not halt at 3.9% of GDP. Because Italy must prevent a return to the growth in debt / GDP to calm the markets, there is less space for expansive economic politics.

On the other hand rumours say that the new government will endanger the economic resources of the NRRP (National Recovery and Resilience Plan). It is a plan approved in 2021 by Italy to help the economy after the stop caused by the pandemic. The figure allocated to Italy is 191 billion (about 10% of Italy GDP). The new government want to reorganise the allocation of the NRRP to deal with the priority problems of Italy. According to experts renegotiate the plan could lead to delays in the disbursement of funds putting at risk the Italian economy.

Any forecast would be uncertain, to analyse this phenomenon more clearly, we would have to wait for the next few days or even the next few weeks.

We wish that the new political stability will encourage stocks and lead them to growth pulling up consequently macroeconomic trends.

コメント